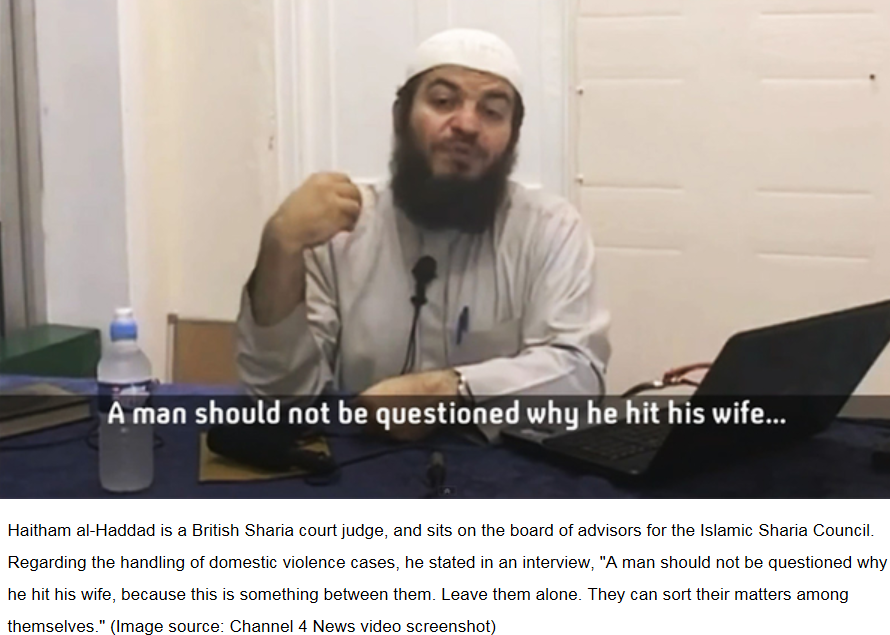

Her er sjarmøren til Islam Net, tatt med skjult kamera av Channel Four.

UK: Sharia Courts Abusing Muslim Women

By Soeren Kern

Muslim women across Britain are being systematically oppressed, abused and discriminated against by Sharia law courts that treat women as second-class citizens, according to a new report, which warns against the spiraling proliferation of Islamic tribunals in the United Kingdom.

The 40-page report, «A Parallel World: Confronting the Abuse of Many Muslim Women in Britain Today,» was authored by Baroness Caroline Cox, a cross-bench member of the British House of Lords and one of the leading defenders of women’s rights in the UK.

The report shows how the increasing influence of Sharia law in Britain today is undermining the fundamental principle that there must be equality for all British citizens under a single law of the land.

The Arbitration Act of 1996 allows parties to resolve certain civil disputes according to Sharia principles in such a way that the decision can be enforced in British courts.

According to the report, however, many Muslim bodies are using the Arbitration Act to support the claim that they are able to make legally binding decisions for members of the Muslim community, when in fact the law limits their role to that of being a mediator to help reach an agreement. «The mediator is not a judge or an arbitrator who imposes a decision,» the report states.

The report shows how Sharia courts often fuse the concepts of arbitration, in which both parties agree to submit their dispute to a mutually agreeable third party for a decision to be made, and mediation, in which the two parties voluntarily use a third party to help them reach an agreement that is acceptable to both sides.

On top of this lies the problem of «jurisdiction creep,» whereby Sharia courts are adjudicating on matters well outside the arbitration framework, such as by deciding cases relating to criminal law, including those involving domestic violence and grievous bodily harm.

As a result, Muslim women, who may lack knowledge of both the English language and their rights under British law, are often pressured by their families to use Sharia courts. These courts often coerce them to sign an agreement to abide by their decisions, which are imposed and viewed as legal judgments.

Worse yet, «Refusal to settle a dispute in a Sharia forum could lead to threats and intimidation, or being ostracized and labelled a disbeliever,» the report states, and adds:

«There is a particular concern that women face pressure to withdraw allegations of domestic violence after they make them. Several women’s groups say they are often reluctant to go to the authorities with women who have run away to escape violence because they cannot trust police officers within the community not to betray the girls to their abusing families.»

The report shows that even in cases where Muslim tribunals work «in tandem» with police investigations, abused women often withdraw their complaints to the police, while Sharia judges let the husbands go unpunished.

Meanwhile, most Sharia courts, when dealing with divorce, do so only in a religious sense. They cannot grant civil divorce; they simply grant a religious divorce in accordance with Sharia law.

According to the report, in many cases this is all that is necessary for a «divorce» anyway; many Muslim women who identify themselves as being «married» are not in marriages that are legally recognized by British law. Although a nikah (an Islamic wedding ceremony) may have taken place, if the marriage is not officially registered, it is not valid in the eyes of civil law. The report states:

«This creates a very serious problem: women who are married in Islamic ceremonies but are not officially married under English law can suffer grave disadvantages because they lack legal protection. What is more, they can be unaware that their marriage is not officially recognized by English law.»

This places Muslim women in an especially precarious legal situation when it comes to divorce. In Islam, a husband does not have to follow the same process as the wife when seeking a talaq (Islamic divorce). He merely has to say «I divorce you» three times, whereas the wife must meet various conditions and pay a fee. The report cites women, when speaking of their own talaq proceedings, who referred to their lack of legal protection after discovering that their nikah did not constitute a valid marriage under English law.

The report cites Kalsoom Bashir, a long-time women’s rights activist in Bristol, who discusses the added problem of polygamy. She notes:

«There is an increasing rise in polygamy within Muslim families and again the women who are involved are not in a position to be able to challenge the situation or get any form of justice. They find it difficult to obtain any maintenance as the marriages are not registered legally. Polygamy is used to control first wives who are told that if they are a problem the man has the Islamic right to take another wife. Sometimes just one of the marriages is registered leaving one wife without any legal protections.»

Overall, the report includes excerpts of testimonies of more than a dozen Muslim women who have suffered abuse and injustice at the hands of Sharia courts in Britain. One woman said: «I feel betrayed by Britain. I came here to get away from this and the situation is worse here than in the country I escaped from.»

The report concludes by calling on the British government to launch a judge-led inquiry to «determine the extent to which discriminatory Sharia law principles are being applied within the UK.» It also calls on the government to support Baroness Cox’s Private Members’ Bill — the Arbitration and Mediation Services (Equality) Bill — which would «create a new criminal offense criminalizing any person who purports to legally adjudicate upon matters which ought to be decided by criminal or family courts.»

Baroness Cox originally introduced the bill in 2011, but it went nowhere due to the lack of support from the main parties. She re-introduced the bill in 2013 and 2014, but it continues to languish, apparently because the main parties are afraid of offending Muslims. Cox has vowed to re-introduce the bill in the next session of Parliament, whose members will be elected on May 7.

The bill aims to combat discrimination by, among other restrictions, prohibiting Sharia courts from: a) treating the evidence of a man as worth more than the evidence of a woman; b) proceeding on the assumption that the division of an estate between male and female children on intestacy must be unequal; or c) proceeding on the assumption that a woman has fewer property rights than a man.

The law would also place a duty on public bodies to ensure that women in polygamous households, or those who have had a religious marriage, are made aware of their legal position and relevant legal rights under British law.

In a letter, Baroness Cox wrote that her recommendations «can by no means remedy all of the sensitive issues involved, but they do offer an important opportunity for redress.» She added that her bill «already has strong support from across the political spectrum in the House of Lords as well as from Muslim women’s groups and other organisations concerned with the suffering of vulnerable women.»

But it remains to be seen whether the next government will agree to support the bill. On March 23, British Home Secretary Theresa May pledged that if the Conservative Party wins the general election, she would launch a review into whether Sharia courts in England and Wales are compatible with British values.

But the Conservative government’s track record on confronting Islam has been patchy at best. In November 2013, for example, the government rejected an amendment offered by Cox to the Anti-Social Behavior, Crime and Policing Bill, which would have protected women who are duped into believing that their marriages are valid under British law when in fact they are not.

More recently, the Conservatives quashed a «politically incorrect» inquiry into the activities of the Muslim Brotherhood in Britain.

While Cox welcomed May’s commitment to investigate Sharia courts, she also expressed concern that politicians will once again bow to political correctness. It is important, she wrote, that such investigations «do not fall at the first hurdle, as appears to have happened with previous, similar government-led reviews. Without powers to subpoena witnesses, any independent review — no matter how well intentioned — will be another lost opportunity.»

Cox summed it up this way:

«The government’s response will be a litmus test of the extent to which it genuinely upholds the principle of equality before the law or is so dominated by the fear of ‘giving offense’ that it will continue to allow these women to suffer in ways which would make our suffragettes turn in their graves.»